My first trip to Nepal shattered many of my preconceived notions. I had expected a more rural and traditional environment, but what I found instead was a densely populated city, full of chaotic traffic, constant noise, and a rhythm that never slows down.

My first trip to Nepal shattered many of my preconceived notions. I had expected a more rural and traditional environment, but what I found instead was a densely populated city, full of chaotic traffic, constant noise, and a rhythm that never slows down.

Kathmandu is anything but quiet. It’s a city where motorbikes weave through streets with no apparent rules, vendors set up wherever space allows, and pedestrians navigate narrow alleyways without traffic lights or sidewalks. What does stand out immediately, though, is the ever-present spiritual atmosphere: small temples, statues of Hindu and Buddhist deities, and the constant scent of incense all form part of the urban landscape.

One of the most striking places I visited was Swayambhunath, also known as the Monkey Temple. This Buddhist site, perched atop a hill, offers breathtaking views of Kathmandu and a dense, layered atmosphere where religious art blends with a population of monkeys that have claimed the site as their own. Beyond the tourists and animals, the focal point is the central stupa—a white dome crowned by the watchful eyes of Buddha gazing in all four directions. The iconography here is bold, symbolic, and omnipresent.

places I visited was Swayambhunath, also known as the Monkey Temple. This Buddhist site, perched atop a hill, offers breathtaking views of Kathmandu and a dense, layered atmosphere where religious art blends with a population of monkeys that have claimed the site as their own. Beyond the tourists and animals, the focal point is the central stupa—a white dome crowned by the watchful eyes of Buddha gazing in all four directions. The iconography here is bold, symbolic, and omnipresent.

I also explored Basantapur Durbar Square, the former royal heart of the city. Despite the damage it sustained during the 2015 earthquake, it remains a key space for understanding the historical depth of the Kathmandu Valley. Its temples, palaces, and sculptures reflect a blend of Newar architecture and Hindu-Buddhist influence. This isn’t a museum—it’s a living space, still in use, still resonating with the weight of history.

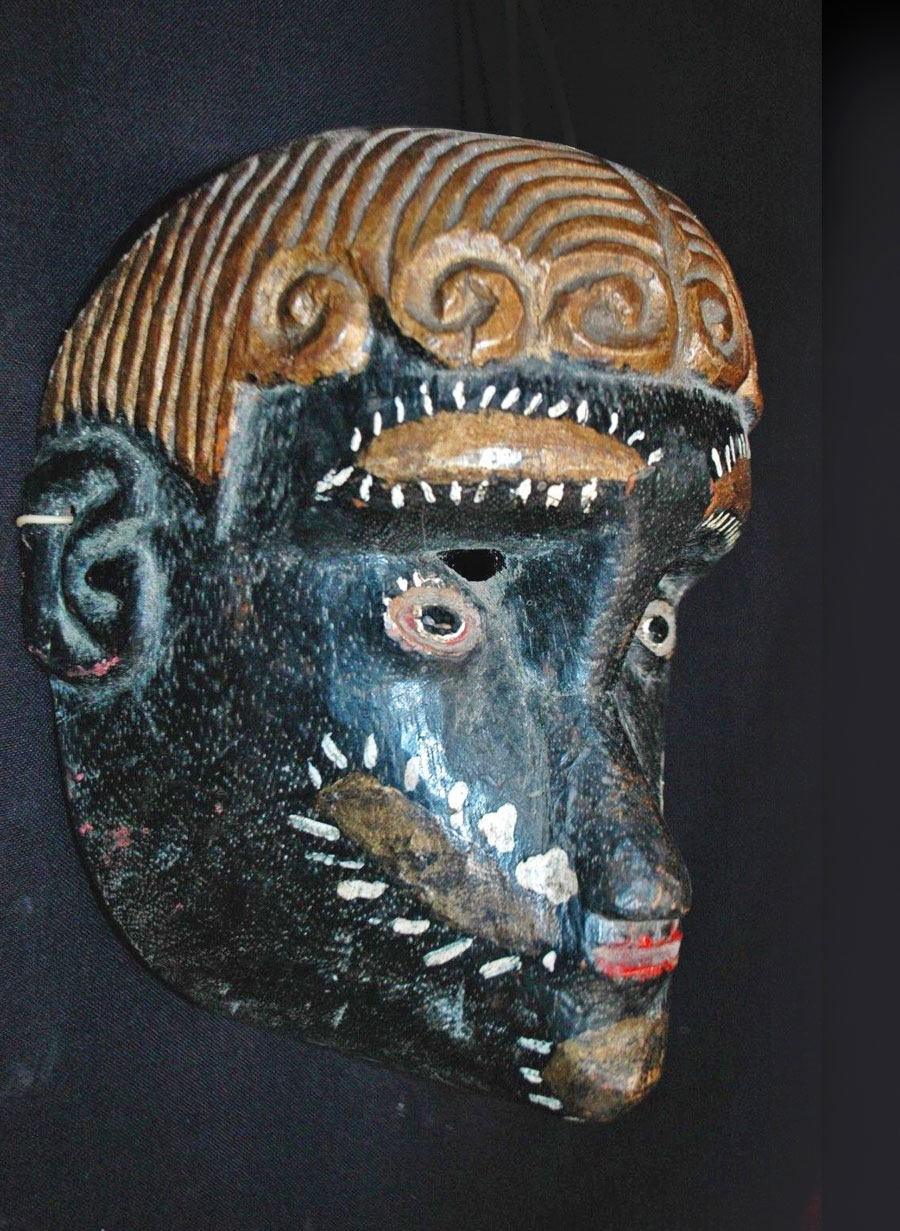

Amid all this, masks are not just decorative objects hanging on walls. In markets and specialized shops, I found everything from mass-produced tourist items to genuine creations made by artisans who travel from rural villages to sell their work in the capital. Some pieces showed Tibetan influence, others adhered to local valley traditions. There were demonic masks,

Amid all this, masks are not just decorative objects hanging on walls. In markets and specialized shops, I found everything from mass-produced tourist items to genuine creations made by artisans who travel from rural villages to sell their work in the capital. Some pieces showed Tibetan influence, others adhered to local valley traditions. There were demonic masks,  protective ones, ritual and theatrical types. What surprised me most was how, in a single stall, authentic works could be mixed in among cheap replicas, with no clear distinction. Identifying a truly authentic mask requires knowledge, experience—and often, intuition.

protective ones, ritual and theatrical types. What surprised me most was how, in a single stall, authentic works could be mixed in among cheap replicas, with no clear distinction. Identifying a truly authentic mask requires knowledge, experience—and often, intuition.

After speaking with several vendors and craftsmen, it became clear that Nepal’s mask-making system is complex. Some artisans work on commission for temples or festivals, while others simply produce what sells to tourists. But even in that commercial context, I found pieces crafted with genuine respect for tradition, symbolism, and the stories these masks are meant to embody.

From my perspective as a collector based in Medellín, Colombia, we often hear the term “Third World” used as if it were a shared category. But this trip reminded me that there are many ways to live and to perceive the world. The cultural, social, and visual differences between Latin America and this part of Asia are vast—but also deeply enriching. The contrast was striking. In Nepal, the presence of ritual and the sacred in everyday life is far more visible. Here, the sacred and the commercial coexist without filter.

we often hear the term “Third World” used as if it were a shared category. But this trip reminded me that there are many ways to live and to perceive the world. The cultural, social, and visual differences between Latin America and this part of Asia are vast—but also deeply enriching. The contrast was striking. In Nepal, the presence of ritual and the sacred in everyday life is far more visible. Here, the sacred and the commercial coexist without filter.

This trip wasn’t just tourism. It was a direct encounter with a living, contradictory, and profoundly symbolic culture. And for someone who has studied masks from afar for years, seeing them in their real context—even amid chaos—was an invaluable lesson.